Poggio Bracciolini on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

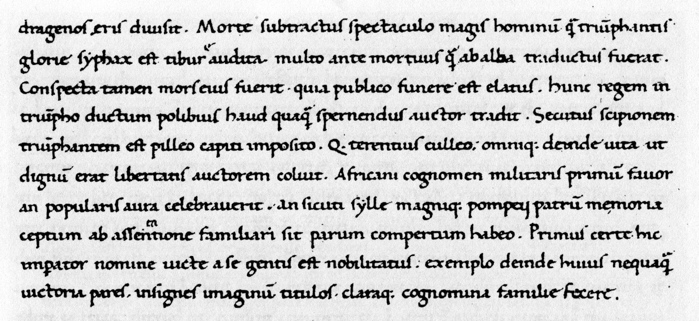

Poggio was famous for his beautiful and legible book hand. The formal humanist script he invented developed into

Poggio was famous for his beautiful and legible book hand. The formal humanist script he invented developed into

Online version

*

1837 edition available online

, the most extensive and authoritative English-language biography to date. * Georg Voigt, ''Wiederbelebung des classischen Alterthums oder das erste Jahrhundert des Humanismus'' (3d ed., Berlin, 1893), gives a good description of Poggio's place in history. *

In Defense of Humanist Aesthetics: Ronald G. Witt’s Study of Early Italian Humanism

, (''H-Net Reviews'', March 2003) * Ronald G. Witt, ''The Two Latin Cultures and the Foundation of Renaissance Humanism in Medieval Italy'' (Cambridge Un. Press, March 2012) * John Winter Jones, trans.,''Travelers in Disguise: Narratives of Eastern Travel by Poggio Bracciolini and Ludovico de Varthema'', (Harvard Un. Press, 1963), intr. by Lincoln Davis Hammond. * John W. Oppel, ''The moral basis of Renaissance politics : a study of the humanistic political and social philosophy of Poggio Bracciolini, 1380-1459'' (Ph.D. thesis, Princeton Un., 1972) * Nancy S. Struever, ''The Language of history in the Renaissance : rhetoric and historical consciousness in Florentine Humanism'' (Princeton Un. Press, 1970) * A. C. de la Mare, ''The handwriting of Italian humanists / Vol. I, fasc. 1, Francesco Petrarca, Giovanni Boccaccio, Coluccio Salutati, Niccolò Niccoli, Poggio Bracciolini, Bartolomeo Aragazzi of Montepulciano, Sozomeno of Pistoia, Giorgio Antonio Vespucci'' (Oxford University Press, 1973) * Louis Paret, ''The annals of Poggio Bracciolini and other forgeries'', (Augustin S.A., 1992) * John Wilson Ross, ''Tacitus and Bracciolini. The Annals forged in the XVth century'', (Diprose & Bateman, 1878) *

Poggio Bracciolini's De Avaritia - A Study in 15th-century Florentine Attitudes Toward Avarice and Usury

' (Thesis, M.A., Sir George Williams Un., Montreal, 1973). Examination of the economic aspects of Poggio's Florentine life. * Remgio Sabbadini,

Le scoperte dei codici latini e greci ne' secoli 14 e 15

', Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1914. Discoveries of Latin and Greek codices in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini (11 February 1380 – 30 October 1459), usually referred to simply as Poggio Bracciolini, was an

Poggio's declining days were spent in the discharge of his prestigious Florentine office—glamorous at first, but soon turned irksome—conducting his intense quarrel with

Poggio's declining days were spent in the discharge of his prestigious Florentine office—glamorous at first, but soon turned irksome—conducting his intense quarrel with

, and Antonio_Beccadelli,_the_author_of_a_scandalous_''Hermaphroditus'',_inspired_by_the_unfettered_eroticism_of_Catullus.html" ;"title="Antonio Beccadelli (poet)">Antonio Beccadelli, the author of a scandalous ''Hermaphroditus'', inspired by the unfettered eroticism of Catullus">Antonio Beccadelli (poet)">Antonio Beccadelli, the author of a scandalous ''Hermaphroditus'', inspired by the unfettered eroticism of Catullus and Martial. All the resources of Poggio's rich vocabulary of the most scurrilous Latin were employed to stain the character of his target; every imaginable crime was imputed to him, and the most outrageous accusations proffered, without any regard to plausibility. Poggio's quarrels against Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

scholar and an early Renaissance humanist

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

. He was responsible for rediscovering and recovering many classical Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

manuscripts, mostly decaying and forgotten in German, Swiss, and French monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

libraries. His most celebrated finds are ''De rerum natura

''De rerum natura'' (; ''On the Nature of Things'') is a first-century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius ( – c. 55 BC) with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some 7 ...

'', the only surviving work by Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

, ''De architectura

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture written by the Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, as a guide f ...

'' by Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled ''De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribute ...

, lost orations by Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

such as '' Pro Sexto Roscio'', Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician from Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilia ...

's ''Institutio Oratoria

''Institutio Oratoria'' (English: Institutes of Oratory) is a twelve-volume textbook on the theory and practice of rhetoric by Roman rhetorician Quintilian. It was published around year 95 AD. The work deals also with the foundational education ...

'', Statius

Publius Papinius Statius (Greek: Πόπλιος Παπίνιος Στάτιος; ; ) was a Greco-Roman poet of the 1st century CE. His surviving Latin poetry includes an epic in twelve books, the ''Thebaid''; a collection of occasional poetry, ...

' ''Silvae

The is a collection of Latin occasional poetry in hexameters, hendecasyllables, and lyric meters by Publius Papinius Statius (c. 45 – c. 96 CE). There are 32 poems in the collection, divided into five books. Each book contains a prose preface ...

'', and Silius Italicus

Tiberius Catius Asconius Silius Italicus (, c. 26 – c. 101 AD) was a Roman senator, orator and Epic poetry, epic poet of the Silver Age of Latin literature. His only surviving work is the 17-book ''Punica (poem), Punica'', an epic poem about th ...

's ''Punica

''Punica'' is a small genus of fruit-bearing deciduous shrubs or small trees in the flowering plant family Lythraceae. The better known species is the pomegranate (''Punica granatum''). The other species, the Socotra pomegranate (''Punica ...

'', as well as works by several minor authors such as Frontinus

Sextus Julius Frontinus (c. 40 – 103 AD) was a prominent Roman civil engineer, author, soldier and senator of the late 1st century AD. He was a successful general under Domitian, commanding forces in Roman Britain, and on the Rhine and Danube ...

' ''De aquaeductu

( en, On aqueducts) is a two-book official report given to the emperor Nerva or Trajan on the state of the List of aqueducts in the city of Rome, aqueducts of Rome, and was written by Sextus Julius Frontinus at the end of the 1st century AD. It ...

'', Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus (occasionally Anglicisation, anglicised as Ammian) (born , died 400) was a Roman soldier and historian who wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from Ancient history, antiquity (preceding Procopius). His w ...

’ ''Res Gestae'' (''Rerum gestarum Libri XXXI''), Nonius Marcellus

Nonius Marcellus was a Roman grammarian of the 4th or 5th century AD. His only surviving work is the ''De compendiosa doctrina'', a dictionary or encyclopedia in 20 books that shows his interests in antiquarianism and Latin literature from Plautus ...

, Probus, Flavius Caper Flavius Caper was a Latin grammarian who flourished during the 2nd century AD.

Caper devoted special attention to the early Latin writers, and is highly spoken of by Priscian

Priscianus Caesariensis (), commonly known as Priscian ( or ), was a L ...

, and Eutyches

Eutyches ( grc, Εὐτυχής; c. 380c. 456) or Eutyches of ConstantinopleArezzo

Arezzo ( , , ) , also ; ett, 𐌀𐌓𐌉𐌕𐌉𐌌, Aritim. is a city and ''comune'' in Italy and the capital of the province of the same name located in Tuscany. Arezzo is about southeast of Florence at an elevation of above sea level. ...

in Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; it, Toscana ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of about 3.8 million inhabitants. The regional capital is Florence (''Firenze'').

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, art ...

, in the village of Terranuova, which in 1862 was renamed Terranuova Bracciolini

Terranuova Bracciolini is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Arezzo in the Italian region Tuscany, located about southeast of Florence and about northwest of Arezzo.

Terranuova Bracciolini borders the following municipalities: Castel ...

in his honor.

Taken by his father to Florence to pursue the studies for which he appeared so apt, he studied Latin under Giovanni Malpaghino of Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the cap ...

, the friend and protégé of Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited w ...

. His distinguished abilities and his dexterity as a copyist of manuscripts brought him into early notice of the chief scholars of Florence; both Coluccio Salutati

Coluccio Salutati (16 February 1331 – 4 May 1406) was an Italian humanist and notary, and one of the most important political and cultural leaders of Renaissance Florence; as chancellor of the Republic and its most prominent voice, he was effec ...

and Niccolò de' Niccoli

Niccolò de' Niccoli (1364 – 22 January 1437) was an Italian Renaissance humanist.

He was born and died in Florence, and was one of the chief figures in the company of learned men which gathered around the patronage of Cosimo de' Medici. Nicc ...

befriended him. He studied notarial law, and, at the age of twenty-one he was received into the Florentine notaries' guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

, the ''Arte dei giudici e notai''.

Career and later life

In October 1403, on high recommendations from Salutati andLeonardo Bruni

Leonardo Bruni (or Leonardo Aretino; c. 1370 – March 9, 1444) was an Italian humanist, historian and statesman, often recognized as the most important humanist historian of the early Renaissance. He has been called the first modern historian. H ...

("Leonardo Aretino"), he entered the service of Cardinal Landolfo Maramaldo, Bishop of Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy a ...

, as his secretary, and a few months later he was invited to join the Chancery of Apostolic Briefs in the Roman Curia of Pope Boniface IX

Pope Boniface IX ( la, Bonifatius IX; it, Bonifacio IX; c. 1350 – 1 October 1404, born Pietro Tomacelli) was head of the Catholic Church from 2 November 1389 to his death in October 1404. He was the second Roman pope of the Western Schism.Richa ...

, thus embarking on 11 turbulent years during which he served under four successive popes (1404–1415), first as ''scriptor'' (writer of official documents), soon moving up to '' abbreviator'', then ''scriptor penitentiarius'', and ''scriptor apostolicus''. Under Martin V

Pope Martin V ( la, Martinus V; it, Martino V; January/February 1369 – 20 February 1431), born Otto (or Oddone) Colonna, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 November 1417 to his death in February 1431. Hi ...

he reached the top rank of his office, as ''Apostolicus Secretarius'', papal secretary. As such he functioned as a personal attendant (''amanuensis'') of the Pope, writing letters at his behest and taking dictation, with no formal registration of the briefs, but merely preserving copies. He was esteemed for his excellent Latin, his extraordinarily beautiful book hand

A book hand was any of several stylized handwriting scripts used during ancient and medieval times. It was intended for legibility and often used in transcribing official documents (prior to the development of printing and similar technologies). ...

, and as occasional liaison with Florence, which involved him in legal and diplomatic work.

Throughout his long career of 50 years, Poggio served a total of seven popes: Boniface IX (1389–1404), Innocent VII (1404–1406), Gregory XII

Pope Gregory XII ( la, Gregorius XII; it, Gregorio XII; – 18 October 1417), born Angelo Corraro, Corario," or Correr, was head of the Catholic Church from 30 November 1406 to 4 July 1415. Reigning during the Western Schism, he was oppose ...

(1406–1415), Antipope John XXIII

Baldassarre Cossa (c. 1370 – 22 December 1419) was Pisan antipope John XXIII (1410–1415) during the Western Schism. The Catholic Church regards him as an antipope, as he opposed Pope Gregory XII whom the Catholic Church now recognizes as ...

(1410–1415), Martin V

Pope Martin V ( la, Martinus V; it, Martino V; January/February 1369 – 20 February 1431), born Otto (or Oddone) Colonna, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 November 1417 to his death in February 1431. Hi ...

(1417–1431), Eugenius IV

Pope Eugene IV ( la, Eugenius IV; it, Eugenio IV; 1383 – 23 February 1447), born Gabriele Condulmer, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 3 March 1431 to his death in February 1447. Condulmer was a Venetian, and ...

(1431–1447), and Nicholas V

Pope Nicholas V ( la, Nicholaus V; it, Niccolò V; 13 November 1397 – 24 March 1455), born Tommaso Parentucelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 March 1447 until his death in March 1455. Pope Eugene made ...

(1447−1455). While he held his office in the ''Curia'' through that momentous period, which saw the Councils of Constance (1414–1418), in the train of Pope John XXIII, and of Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

(1431–1449), and the final restoration of the papacy under Nicholas V (1447), he was never attracted to the ecclesiastical life (and the lure of its potential riches). In spite of his meager salary in the Curia, he remained a layman to the end of his life.

The greater part of Poggio's long life was spent in attendance to his duties in the Roman Curia at Rome and the other cities the pope was constrained to move his court. Although he spent most of his adult life in his papal service, he considered himself a Florentine working for the papacy. He actively kept his links to Florence and remained in constant communication with his learned and influential Florentine friends: Coluccio Salutati

Coluccio Salutati (16 February 1331 – 4 May 1406) was an Italian humanist and notary, and one of the most important political and cultural leaders of Renaissance Florence; as chancellor of the Republic and its most prominent voice, he was effec ...

(1331–1406), Niccolò de' Niccoli

Niccolò de' Niccoli (1364 – 22 January 1437) was an Italian Renaissance humanist.

He was born and died in Florence, and was one of the chief figures in the company of learned men which gathered around the patronage of Cosimo de' Medici. Nicc ...

(1364–1437), Lorenzo de' Medici the elder

Lorenzo the Elder (c. 1395 – 23 September 1440) was an Italian banker of the House of Medici of Florence, the younger brother of Cosimo de' Medici the Elder and progenitor of the so-called "Popolani" ("populist, i.e. for the people") line of ...

(1395–1440), Leonardo Bruni (Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, 1369–1444), Carlo Marsuppini

Carlo Marsuppini (1399–1453), also known as Carlo Aretino and Carolus Arretinus, was an Italian Renaissance humanist and chancellor of the Florentine Republic.

Biography

Marsuppini was born in Genoa into a family from Arezzo, but grew up and ...

("Carlo Aretino", Chancellor, 1399–1453), and Cosimo de' Medici

Cosimo di Giovanni de' Medici (27 September 1389 – 1 August 1464) was an Italian banker and politician who established the Medici family as effective rulers of Florence during much of the Italian Renaissance. His power derived from his wealth ...

(1389–1464).

In England

After Martin V was elected as the new pope in November 1417, Poggio, although not holding any office, accompanied his court toMantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard language, Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and ''comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture ...

in late 1418, but, once there, decided to accept the invitation of Henry, Cardinal Beaufort, bishop of Winchester, to go to England. His five years spent in England, until returning to Rome in 1423, were the least productive and satisfactory of his life.

In Florence

Poggio resided in Florence during 1434−36 with Eugene IV. On the proceeds of a sale of a manuscript ofLivy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Ancient Rome, Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditiona ...

in 1434, he built himself a villa in the Valdarno

The Valdarno is the valley of the river Arno, although this name does not apply to the entire river basin. Usage of the term generally excludes Casentino and the valleys formed by major tributaries.

Some towns in the area:

*Rignano sull'Arno

*Fi ...

, which he adorned with a collection of antique sculpture (notably a series of busts meant to represent thinkers and writers of antiquity), coins and inscriptions, works that were familiar to his friend Donatello

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi ( – 13 December 1466), better known as Donatello ( ), was a Republic of Florence, Florentine sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Republic of Florence, Florence, he studied classical sculpture and use ...

.

In December 1435, at age 56, tired of the unstable character of his single life, Poggio left his long-term mistress and delegitimized the fourteen children he had had with her, scoured Florence for a wife, and married a girl of a noble Florentine family, not yet 18, Selvaggia dei Buondelmonti. In spite of the remonstrances and dire predictions of all his friends about the age discrepancy, the marriage was a happy one, producing five sons and a daughter. Poggio wrote a spate of long letters to justify his move, and composed one of his famous dialogues, ''An Seni Sit uxor ducenda'' (''Whether an old man should marry'', 1436).

Poggio also lived in Florence during the Council of Florence

The Council of Florence is the seventeenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held between 1431 and 1449. It was convoked as the Council of Basel by Pope Martin V shortly before his death in February 1431 and took place in ...

, from 1439 to 1442.

Dispute with Valla

In his quarrel againstLorenzo Valla

Lorenzo Valla (; also Latinized as Laurentius; 14071 August 1457) was an Italian Renaissance humanist, rhetorician, educator, scholar, and Catholic priest. He is best known for his historical-critical textual analysis that proved that the ''Don ...

—an expert at philological analysis of ancient texts, a redoubtable opponent endowed with a superior intellect, and a hot temperament fitted to protracted disputation—Poggio found his match.Lodi Nauta, "Lorenzo Valla", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP, 2009) Poggio started in February 1452 with a full-dress critique of the ''Elegantiae'', Valla's major work on Latin language and style, where he supported a critical use of Latin ''eruditio'' going beyond pure admiration and respectful ''imitatio'' of the classics.

At stake was the new approach of the ''humanae litterae'' (profane classical Greek and Latin literature) in relation to the ''divinae litterae'' (biblical exegesis of the Judeo-Christian "sacred scriptures"). Valla argued that biblical texts could be subjected to the same philological criticism as the great classics of antiquity. Poggio held that humanism and theology were separate fields of inquiry, and labeled Valla's ''mordacitas'' (radical criticism) as ''dementia''.

Poggio's series of five ''Orationes in Laurentium Vallam'' (re-labeled ''Invectivae'' by Valla) were countered, line by line, by Valla's ''Antidota in Pogium'' (1452−53). It is remarkable that eventually the belligerents acknowledged their talents, gained their mutual respect, and prompted by Filelfo, reconciled, and became good friends. Shepherd finely comments on Valla's advantage in the literary dispute: the power of irony and satire (making a sharp imprint on memory) versus the ploddingly heavy dissertation (that is quickly forgotten). These sportive polemics among the early Italian humanists were famous, and spawned a literary fashion in Europe which reverberated later, for instance, in Scaliger

The Della Scala family, whose members were known as Scaligeri () or Scaligers (; from the Latinized ''de Scalis''), was the ruling family of Verona and mainland Veneto (except for Venice) from 1262 to 1387, for a total of 125 years.

History

Wh ...

's contentions with Scioppius and Milton

Milton may refer to:

Names

* Milton (surname), a surname (and list of people with that surname)

** John Milton (1608–1674), English poet

* Milton (given name)

** Milton Friedman (1912–2006), Nobel laureate in Economics, author of '' Free t ...

's with Salmasius

Claude Saumaise (15 April 1588 – 3 September 1653), also known by the Latin name Claudius Salmasius, was a French classical scholar.

Life

Salmasius was born at Semur-en-Auxois in Burgundy. His father, a counsellor of the parlement of Dijon, se ...

.

Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' wa ...

, in 1505, discovered Lorenzo Valla's ''Adnotationes in Novum Testamentum'' (''New Testament Notes''), which encouraged him to pursue the textual criticism of the Holy Scriptures, free of all academic entanglements that might cramp or hinder his scholarly independence—contributing to Erasmus's stature of leading Dutch Renaissance humanist.

In his introduction, Erasmus declared his support of Valla's thesis against the ''invidia'' of envious scholars such as Poggio, whom he unfairly described as "a petty clerk so uneducated that even if he were not indecent he would still not be worth reading, and so indecent that he would deserve to be rejected by good men however learned he was." (Quoted in Salvatore I. Camporeale in his essay on the Poggio–Lorenzo dispute).

Later years and death

After the death in April 1453 of his intimate friend Carlo Aretino, who had been theChancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

of the Florentine Republic, the choice of his replacement, mostly dictated by Cosimo de' Medici, fell upon Poggio. He resolved to retire from his service of 50 years in the Chancery of Rome, and returned to Florence to assume this new function. This coincided with the news of the fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

to the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

.

Poggio's declining days were spent in the discharge of his prestigious Florentine office—glamorous at first, but soon turned irksome—conducting his intense quarrel with

Poggio's declining days were spent in the discharge of his prestigious Florentine office—glamorous at first, but soon turned irksome—conducting his intense quarrel with Lorenzo Valla

Lorenzo Valla (; also Latinized as Laurentius; 14071 August 1457) was an Italian Renaissance humanist, rhetorician, educator, scholar, and Catholic priest. He is best known for his historical-critical textual analysis that proved that the ''Don ...

, editing his correspondence for publication, and in the composition of his history of Florence. He died in 1459 before he could put the final polish to his work, and was buried in the church of Santa Croce. A statue by Donatello

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi ( – 13 December 1466), better known as Donatello ( ), was a Republic of Florence, Florentine sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Republic of Florence, Florence, he studied classical sculpture and use ...

and a portrait by Antonio del Pollaiuolo

Antonio del Pollaiuolo ( , , ; 17 January 1429/14334 February 1498), also known as Antonio di Jacopo Pollaiuolo or Antonio Pollaiuolo (also spelled Pollaiolo), was an Italian painter, sculptor, engraver, and goldsmith during the Italian Rena ...

remain to commemorate a citizen who chiefly for his services to humanistic

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

literature deserved the notice of posterity. During his life, Poggio kept acquiring properties around Florence and invested in the city enterprises with the Medici bank

The Medici Bank (Italian: ''Banco dei Medici'' ) was a financial institution created by the Medici family in Italy during the 15th century (1397–1494). It was the largest and most respected bank in Europe during its prime. There are some estima ...

. At his death, his gross assets amounted to 8,500 florins, with only 137 families in Florence owning more capital. His wife, five sons and daughter all survived him.

Search for manuscripts

After July 1415—Antipope John XXIII

Baldassarre Cossa (c. 1370 – 22 December 1419) was Pisan antipope John XXIII (1410–1415) during the Western Schism. The Catholic Church regards him as an antipope, as he opposed Pope Gregory XII whom the Catholic Church now recognizes as ...

had been deposed by the Council of Constance and the Roman Pope Gregory XII

Pope Gregory XII ( la, Gregorius XII; it, Gregorio XII; – 18 October 1417), born Angelo Corraro, Corario," or Correr, was head of the Catholic Church from 30 November 1406 to 4 July 1415. Reigning during the Western Schism, he was oppose ...

had abdicated—the papal office remained vacant for two years, which gave Poggio some leisure time in 1416/17 for his pursuit of manuscript hunting. In the spring of 1416 (sometime between March and May), Poggio visited the baths at the German spa of Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden is ...

. In a long letter to Niccoli (p. 59−68) he reported his discovery of an "Epicurean" lifestyle—one year before finding Lucretius—where men and women bathe together, barely separated, in minimum clothing: "I have related enough to give you an idea what a numerous school of Epicureans is established in Baden. I think this must be the place where the first man was created, which the Hebrews call the garden of pleasure. If pleasure can make a man happy, this place is certainly possessed of every requisite for the promotion of felicity." (p. 66)

Poggio was marked by the passion of his teachers for books and writing, inspired by the first generation of Italian humanists centered around Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), who had revived interest in the forgotten masterpieces of Livy and Cicero, Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was somet ...

(1313–1375) and Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406). Poggio joined the second generation of civic humanists forming around Salutati. Resolute in glorifying ''studia humanitatis'' (the study of "humanities", a phrase popularized by Leonardo Bruni), learning (''studium''), literacy (''eloquentia''), and erudition (''eruditio'') as the chief concern of man, Poggio ridiculed the folly of popes and princes, who spent their time in wars and ecclesiastical disputes instead of reviving the lost learning of antiquity.

The literary passions of the learned Italians in the new Humanist Movement

The Humanist Movement is an international volunteer organisation following and spreading the ideas of Argentine writer Mario Rodríguez Cobos, commonly known by his nickname "Silo". The movement's ideology is known as New Humanism, Universal Hu ...

, which were to influence the future course of both Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

and Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, were epitomized in the activities and pursuits of this self-made man

"Self-made man" is a classic phrase coined on February 2, 1842 by Henry Clay in the United States Senate, to describe individuals whose success lay within the individuals themselves, not with outside conditions. Benjamin Franklin, one of the Foun ...

, who rose from the lowly position of scribe in the Roman Curia to the privileged role of apostolic secretary.

He became devoted to the revival of classical studies amid conflicts of popes and antipopes, cardinals and councils, in all of which he played an official part as first-row witness, chronicler and (often unsolicited) critic and adviser.

Thus, when his duties called him to the Council of Constance in 1414, he employed his forced leisure in exploring the libraries of Swiss and Swabia

Swabia ; german: Schwaben , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of ...

n abbeys. His great manuscript finds date to this period, 1415−1417. The treasures he brought to light at Reichenau, Weingarten, and above all St. Gall, retrieved from the dust and abandon many lost masterpieces of Latin literature, and supplied scholars and students with the texts of authors whose works had hitherto been accessible only in fragmented or mutilated copies.

St. Gallen

In his epistles he described how he recoveredCicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

's '' Pro Sexto Roscio'', Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician from Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilia ...

, Statius

Publius Papinius Statius (Greek: Πόπλιος Παπίνιος Στάτιος; ; ) was a Greco-Roman poet of the 1st century CE. His surviving Latin poetry includes an epic in twelve books, the ''Thebaid''; a collection of occasional poetry, ...

' ''Silvae

The is a collection of Latin occasional poetry in hexameters, hendecasyllables, and lyric meters by Publius Papinius Statius (c. 45 – c. 96 CE). There are 32 poems in the collection, divided into five books. Each book contains a prose preface ...

'', part of Gaius Valerius Flaccus

Gaius Valerius Flaccus (; died ) was a 1st-century Roman poet who flourished during the " Silver Age" under the Flavian dynasty, and wrote a Latin ''Argonautica'' that owes a great deal to Apollonius of Rhodes' more famous epic.St. Gallen

, neighboring_municipalities = Eggersriet, Gaiserwald, Gossau, Herisau (AR), Mörschwil, Speicher (AR), Stein (AR), Teufen (AR), Untereggen, Wittenbach

, twintowns = Liberec (Czech Republic)

, website ...

. He also recovered Silius Italicus

Tiberius Catius Asconius Silius Italicus (, c. 26 – c. 101 AD) was a Roman senator, orator and Epic poetry, epic poet of the Silver Age of Latin literature. His only surviving work is the 17-book ''Punica (poem), Punica'', an epic poem about th ...

's ''Punica

''Punica'' is a small genus of fruit-bearing deciduous shrubs or small trees in the flowering plant family Lythraceae. The better known species is the pomegranate (''Punica granatum''). The other species, the Socotra pomegranate (''Punica ...

'', Marcus Manilius

Marcus Manilius (fl. 1st century AD) was a Roman poet, astrologer, and author of a poem in five books called '' Astronomica''.

The ''Astronomica''

The author of ''Astronomica'' is neither quoted nor mentioned by any ancient writer. Even his ...

's '' Astronomica'', and Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled ''De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribute ...

's ''De architectura

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture written by the Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, as a guide f ...

''. The manuscripts were then copied, and communicated to the learned. He carried on the same untiring research in many Western European countries.

Cluny Abbey

In 1415 atCluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in 9 ...

he found Cicero's complete great forensic orations, previously only partially available.

Langres

AtLangres

Langres () is a commune in France, commune in northeastern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture of the Departments of France, department of Haute-Marne, in the Regions of France, region of Grand Est.

History

As the capital o ...

in the summer of 1417 he discovered Cicero's ''Oration for Caecina'' and nine other hitherto unknown orations of Cicero's.

Monte Cassino

AtMonte Cassino

Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Latin Valley, Italy, west of Cassino and at an elevation of . Site of the Roman town of Casinum, it is widely known for its abbey, the first h ...

, in 1425, a manuscript of Frontinus

Sextus Julius Frontinus (c. 40 – 103 AD) was a prominent Roman civil engineer, author, soldier and senator of the late 1st century AD. He was a successful general under Domitian, commanding forces in Roman Britain, and on the Rhine and Danube ...

' late first century ''De aquaeductu

( en, On aqueducts) is a two-book official report given to the emperor Nerva or Trajan on the state of the List of aqueducts in the city of Rome, aqueducts of Rome, and was written by Sextus Julius Frontinus at the end of the 1st century AD. It ...

'' on the ancient aqueducts of Rome

The Romans constructed aqueducts throughout their Republic and later Empire, to bring water from outside sources into cities and towns. Aqueduct water supplied public baths, latrines, fountains, and private households; it also supported mining o ...

. He was also credited with having recovered Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus (occasionally Anglicisation, anglicised as Ammian) (born , died 400) was a Roman soldier and historian who wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from Ancient history, antiquity (preceding Procopius). His w ...

’ ''Res Gestae'' (''Rerum gestarum Libri XXXI''), Nonius Marcellus

Nonius Marcellus was a Roman grammarian of the 4th or 5th century AD. His only surviving work is the ''De compendiosa doctrina'', a dictionary or encyclopedia in 20 books that shows his interests in antiquarianism and Latin literature from Plautus ...

, Probus, Flavius Caper Flavius Caper was a Latin grammarian who flourished during the 2nd century AD.

Caper devoted special attention to the early Latin writers, and is highly spoken of by Priscian

Priscianus Caesariensis (), commonly known as Priscian ( or ), was a L ...

and Eutyches

Eutyches ( grc, Εὐτυχής; c. 380c. 456) or Eutyches of ConstantinopleHersfeld Abbey

Hersfeld Abbey was an important Benedictine imperial abbey in the town of Bad Hersfeld in Hesse (formerly in Hesse-Nassau), Germany, at the confluence of the rivers Geisa, Haune and Fulda. The ruins are now a medieval festival venue.

History

H ...

.

''De rerum natura''

Poggio's most famous find was the discovery of the only surviving manuscript ofLucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

's ''De rerum natura

''De rerum natura'' (; ''On the Nature of Things'') is a first-century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius ( – c. 55 BC) with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some 7 ...

'' (''"On the Nature of Things"'') known at the time, in a German monastery (never named by Poggio, but probably Fulda

Fulda () (historically in English called Fuld) is a town in Hesse, Germany; it is located on the river Fulda and is the administrative seat of the Fulda district (''Kreis''). In 1990, the town hosted the 30th Hessentag state festival.

History ...

), in January 1417. Poggio spotted the name, which he remembered as quoted by Cicero. This was a Latin poem of 7,400 lines, divided into six books, giving a full description of the world as viewed by the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus

Epicurus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκουρος ; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influenced ...

(see Epicureanism

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by Epi ...

).

The manuscript found by Poggio is not extant, but fortunately, he sent the copy to his friend Niccolò de' Niccoli

Niccolò de' Niccoli (1364 – 22 January 1437) was an Italian Renaissance humanist.

He was born and died in Florence, and was one of the chief figures in the company of learned men which gathered around the patronage of Cosimo de' Medici. Nicc ...

, who made a transcription in his renowned book hand (as Niccoli was the creator of italic script

Italic script, also known as chancery cursive and Italic hand, is a semi-cursive, slightly sloped style of handwriting and calligraphy that was developed during the Renaissance in Italy. It is one of the most popular styles used in contemporary ...

), which became the model for the more than fifty other copies circulating at the time. Poggio would later complain that Niccoli had not returned his original copy for 14 years. Later, two 9th-century manuscripts were discovered, the O (the Codex Oblongus, copied c. 825) and Q (the Codex Quadratus), now kept at Leiden University

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; nl, Universiteit Leiden) is a Public university, public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. The university was founded as a Protestant university in 1575 by William the Silent, William, Prince o ...

. The book was first printed in 1473.

The Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

-winning 2011 book '' The Swerve: How the World Became Modern'' by Stephen Greenblatt

Stephen Jay Greenblatt (born November 7, 1943) is an American Shakespearean, literary historian, and author. He has served as the John Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University since 2000. Greenblatt is the general edit ...

is a narrative of the discovery of the old Lucretius manuscript by Poggio. Greenblatt analyzes the poem's subsequent impact on the development of the Renaissance, the Reformation, and modern science.

Friends

Poggio cultivated and maintained throughout his life close friendships with some of the most important learned men of the age:Niccolò de' Niccoli

Niccolò de' Niccoli (1364 – 22 January 1437) was an Italian Renaissance humanist.

He was born and died in Florence, and was one of the chief figures in the company of learned men which gathered around the patronage of Cosimo de' Medici. Nicc ...

(the inventor of the italic script

Italic script, also known as chancery cursive and Italic hand, is a semi-cursive, slightly sloped style of handwriting and calligraphy that was developed during the Renaissance in Italy. It is one of the most popular styles used in contemporary ...

), Leonardo Bruni ("Leonardo Aretino"), Lorenzo and Cosimo de' Medici, Carlo Marsuppini ("Carlo Aretino"), Guarino Veronese

Guarino Veronese or Guarino da Verona (1374 – 14 December 1460) was an Italian classical scholar, humanist, and translator of ancient Greek texts during the Renaissance. In the republics of Florence and Venice he studied under Manuel Chrysolor ...

, Ambrogio Traversari, Francesco Barbaro, Francesco Accolti Francesco Accolti (c. 1416 – 1488), also called Francesco d'Arezzo, was an Italian jurist. The brother of Benedetto Accolti, he professed jurisprudence at Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bonon ...

, Feltrino Boiardo, Lionello d'Este

Leonello d'Este (also spelled Lionello; 21 September 1407 – 1 October 1450) was Marquess of Ferrara, Modena, and Reggio Emilia from 1441 to 1450. Despite the presence of legitimate children, Leonello was favoured by his father as his succes ...

(who became Marquis of Ferrara

Ferrara (, ; egl, Fràra ) is a city and ''comune'' in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital of the Province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream ...

, 1441–1450), and many others, who all shared his passion for retrieving the manuscripts and art of the ancient Greco-Roman world. His early friendship with Tommaso da Sarzana stood Poggio in good stead when his learned friend was elected pope, under the name of Nicolas V (1447−1455), a proven protector of scholars and an active sponsor of learning, who founded the Vatican library

The Vatican Apostolic Library ( la, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, it, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana), more commonly known as the Vatican Library or informally as the Vat, is the library of the Holy See, located in Vatican City. Formally es ...

in 1448 with 350 codices.

These learned men were adept at maintaining an extended network of personal relations among a circle of talented and energetic scholars in which constant communication was secured by an immense traffic of epistolary exchanges.

They were bent on creating a rebirth of intellectual life for Italy by means of a vital reconnection with the texts of antiquity. Their worldview was eminently characteristic of Italian humanism

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

in the earlier Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

, which eventually spread all over Western Europe and led to the full Renaissance and the Reformation, announcing the modern age.

Legacy

Works

Poggio, like Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (who becamePius II

Pope Pius II ( la, Pius PP. II, it, Pio II), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini ( la, Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus, links=no; 18 October 1405 – 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 August ...

), was a great traveller, and wherever he went he brought enlightened powers of observation trained in liberal studies to bear upon the manners of the countries he visited. We owe to his pen curious remarks on English and Swiss customs, valuable notes on the remains of ancient monuments in Rome, and a singularly striking portrait of Jerome of Prague

Jerome of Prague ( cs, Jeroným Pražský; la, Hieronymus Pragensis; 1379 – 30 May 1416) was a Czech scholastic philosopher, theologian, reformer, and professor. Jerome was one of the chief followers of Jan Hus and was burned for heresy at ...

as he appeared before the judges who condemned him to the stake.

In literature he embraced the whole sphere of contemporary studies, and distinguished himself as an orator, a writer of rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

al treatises, a panegyrist

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of grc, ...

of the dead, a passionate impugner of the living, a sarcastic polemist, a translator from the Greek, an epistolographer and grave historian and a facetious compiler of ''fabliaux

A ''fabliau'' (; plural ''fabliaux'') is a comic, often anonymous tale written by jongleurs in northeast France between c. 1150 and 1400. They are generally characterized by sexual and scatological obscenity, and by a set of contrary attitudes� ...

'' in Latin.

His cultural/social/moral essays covered a wide range of subjects concerning the interests and values of his time:

* ''De avaritia'' (''On Greed'', 1428−29) - Poggio's first major work. The old school of biographers (Shepherd, Walser) and historians saw in it a traditional condemnation of avarice. Modern historians tend, on the contraryespecially if studying the economic growth of the Italian Trecento

The Trecento (, also , ; short for , "1300") refers to the 14th century in Italian cultural history.

Period Art

Commonly, the Trecento is considered to be the beginning of the Renaissance in art history. Painters of the Trecento included Giotto ...

and Quattrocento

The cultural and artistic events of Italy during the period 1400 to 1499 are collectively referred to as the Quattrocento (, , ) from the Italian word for the number 400, in turn from , which is Italian for the year 1400. The Quattrocento encom ...

to read it as a precocious statement of early capitalism, at least in its Florentine form — breaking through the hold of medieval values that disguised the realities of interest and loans in commerce to proclaim the social utility of wealth. It is the voice of a new age linking wealth, personal worth, conspicuous expenditure, ownership of valuable goods and objects, and social status, a voice not recognized until the late 20th century.;

* ''An seni sit uxor ducenda'' (''On Marriage in Old Age'', 1436);

* ''De infelicitate principum'' (''On the Unhappiness of Princes'', 1440);

* ''De nobilitate'' (''On Nobility'', 1440): Poggio, a self-made man, defends true nobility as based on virtue rather than birth, an expression of the meritocracy

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods and/or political power are vested in individual people based on talent, effort, and achiev ...

favored by the rich bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

;

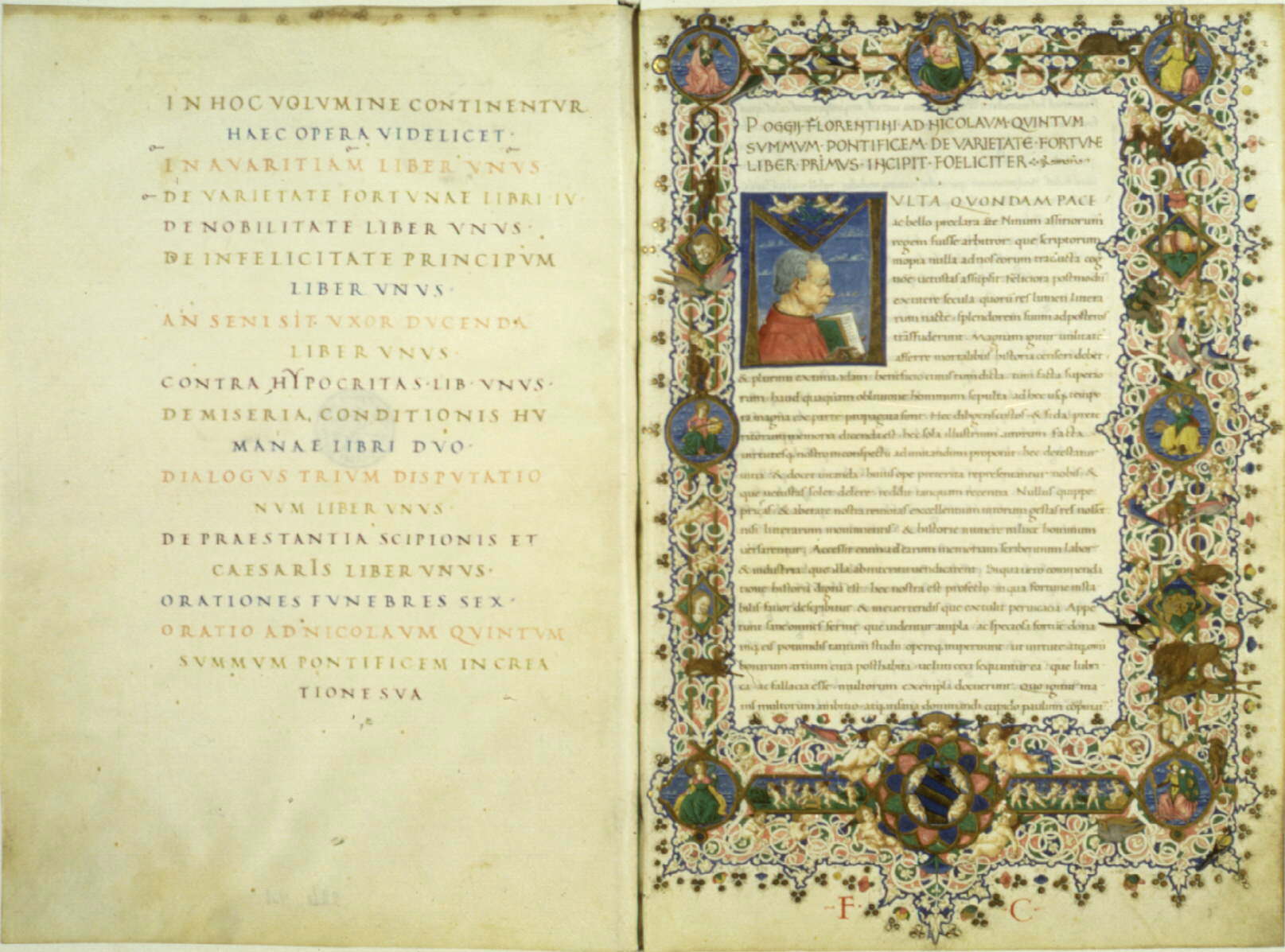

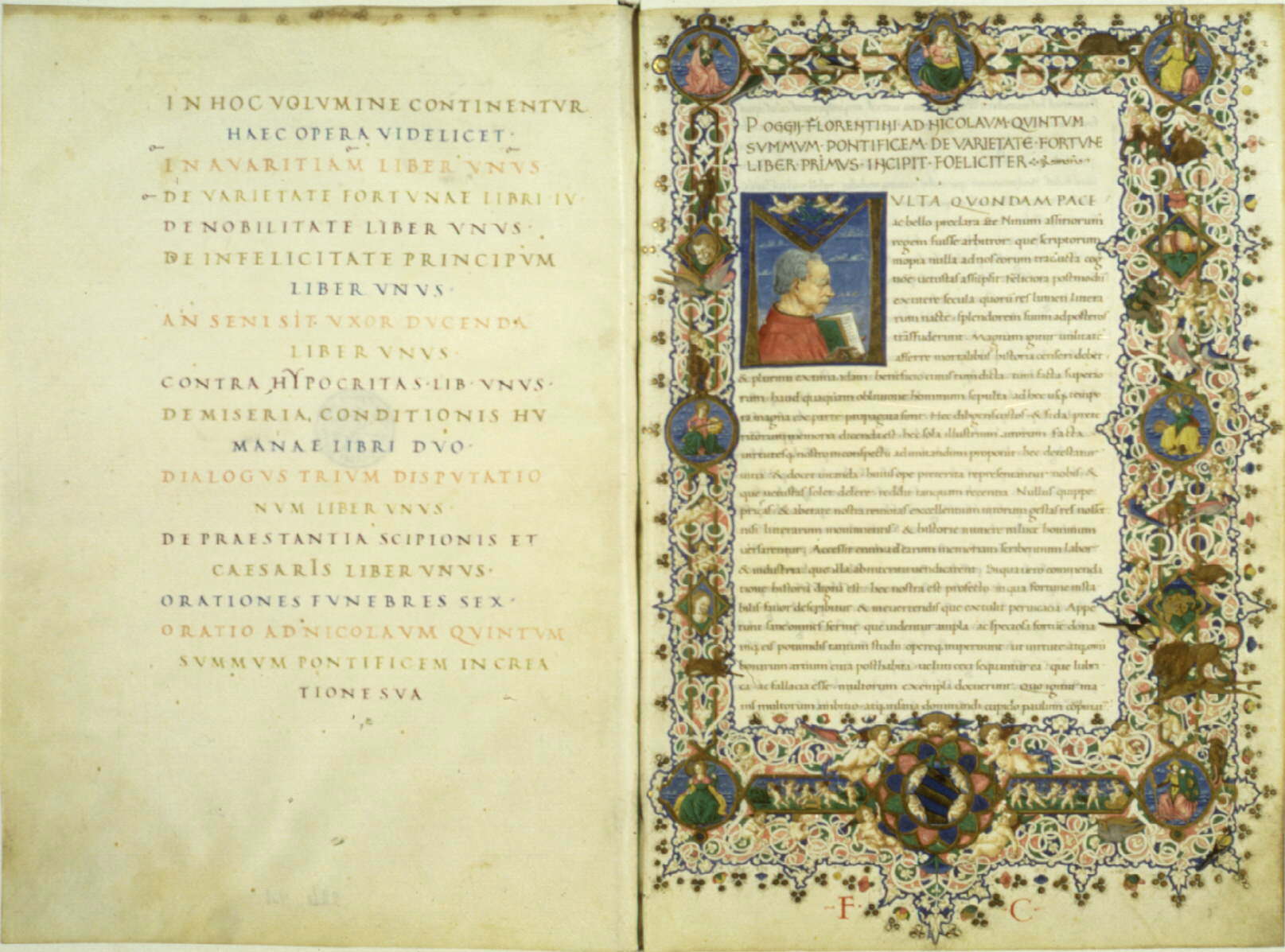

* ''De varietate fortunae'' (''On the Vicissitudes of Fortune'', 1447);

* ''Contra hypocritas'' (''Against Hypocrisy'', 1448);

* ''Historia disceptativa convivialis'' (Historical discussions between guests after a meal) in three parts (1450):

: 1) on expressions of thanks

: 2) on the dignity of medical versus legal profession (a reprise of Salutati's 1398 treatment of the same subject, ''De Nobilitate Legum et Medicinae''): Niccolo Niccoli, appealing to the lessons of experience, is arguing that laws are imposed by the will of the stronger to hold the state together − not God-given to rulers, nor a fact of nature − leading biographer Ernst Walser to conclude that "Poggio, in his writing, presents Machiavellism before Machiavelli."

: 3) on literate Latin versus vernacular Latin in classical Rome; Poggio concludes that they were both the same language, not two distinct idioms.

* ''De miseria humanae conditionis'' (''On the Misery of Human Life'', 1455), reflections in his retirement in Florence inspired by the sack of Constantinople.

These compositions, all written in Latin − and reviving the classical form of dialogues, between himself and learned friends − belonged to a genre of socratic reflections which, since Petrarch set the fashion, was highly praised by Italian men of letters and made Poggio famous throughout Italy. They exemplify his conception of ''studia humanitatis

The Latin school was the grammar school of 14th- to 19th-century Europe, though the latter term was much more common in England. Emphasis was placed, as the name indicates, on learning to use Latin. The education given at Latin schools gave gre ...

'' as an epitome of human knowledge and wisdom reserved only to the most learned, and the key to what the ancient philosophers called "virtue" and "the good". And thus, they are invaluable windows into the knowledge and Weltanschauung

A worldview or world-view or ''Weltanschauung'' is the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge, culture, and point of view. A worldview can include natural p ...

of his age − geography, history, politics, morals, social aspects — and the emergence of the new values of the "Humanist Movement". They are loaded with rich nuggets of fact embedded in subtle disquisitions, with insightful comments, brilliant illustrations, and a wide display of historical and contemporary references. Poggio was always inclined to make objective observations and clinical comparisons between various cultural mores, for instance ancient Roman practices versus modern ones, or Italians versus the English. He compared the eloquence of Jerome of Prague and his fortitude before death with ancient philosophers. The abstruse points of theology presented no interest to him, only the social impact of the Church did, mostly as an object of critique and ridicule. ''On the Vicissitudes of Fortune'' became famous for including in book IV an account of the 25-year voyage of the Venetian adventurer Niccolo de' Conti in Persia and India, which was translated into Portuguese on express command of the Portuguese King Emmanuel I. An Italian translation was made from the Portuguese.

Poggio's ''Historia Florentina'' (''History of Florence''), is a history of the city from 1350 to 1455, written in avowed imitation of Livy and Sallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (; 86 – ), was a Roman historian and politician from an Italian plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became during the 50s BC a partisan o ...

, and possibly Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of "scientifi ...

(available in Greek, but translated into Latin by Valla only in 1450–52) in its use of speeches to explain decisions. Poggio continued Leonardo Bruni's ''History of the Florentine People'', which closed in 1402, and is considered the first modern history book. Poggio limited his focus to external events, mostly wars, in which Florence was the ''defensor Tusciae'' and of Italian liberty. But Poggio also pragmatically defended Florence's expansionist policies to insure the "safety of the Florentine Republic", which became the key motive of its history, as a premonition of Machiavelli's doctrine. Conceding to superior forces becomes an expression of reason and advising it a mark of wisdom. His intimate and vast experience of Italian affairs inculcated in him a strong sense of realism, echoing his views on laws expressed in his second ''Historia disceptativa convivialis (1450)''. Poggio's beautiful rhetorical prose turns his ''Historia Florentina'' into a vivid narrative, with a sweeping sense of movement, and a sharp portrayal of the main characters, but it also exemplifies the limitations of the newly emerging historical style, which, in the work of Leonardo Bruni, Carlo Marsuppini and Pietro Bembo

Pietro Bembo, ( la, Petrus Bembus; 20 May 1470 – 18 January 1547) was an Italian scholar, poet, and literary theorist who also was a member of the Knights Hospitaller, and a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. As an intellectual of the It ...

, retained "romantic" aspects and did not reach yet the weight of objectivity later expected by the school of modern historians (especially since 1950).

His ''Liber Facetiarum'' (1438−1452), or ''Facetiae

The ''Facetiae'' is an anthology of jokes by Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459), first published in 1470. It was the first printed joke book. The collection, "the most famous jokebook of the Renaissance", is notable for its inclusion of scatological ...

'', a collection of humorous and indecent tales expressed in the purest Latin Poggio could command, are the works most enjoyed today: they are available in several English translations. This book is chiefly remarkable for its unsparing satires on the monastic orders and the secular clergy. "The worst men in the world live in Rome, and worse than the others are the priests, and the worst of the priests they make cardinals, and the worst of all the cardinals is made pope." Poggio's book became an internationally popular work in all countries of Western Europe, and has gone through multiple editions until modern times.

In addition Poggio's works included his ''Epistolae'', a collection of his letters, a most insightful witness of his remarkable age, in which he gave full play to his talent as chronicler of events, to his wide range or interests, and to his most acerbic critical sense.

Revival of Latin and Greek

In the way of many humanists of his time, Poggio rejected the vernacular Italian and always wrote only in Latin, and translated works from Greek into that language. His letters are full of learning, charm, detail, and amusing personal attack on his enemies and colleagues. It is also noticeable as illustrating the Latinizing tendency of an age which gave classic form to the lightest essays of the fancy. Poggio was a fluent and copious writer in Latin, admired for his classical style inspired from Cicero, if not fully reaching the elegance of his model, but outstanding by the standards of his age. Italy was barely emerging from what Petrarch had termed the Dark Ages, while Poggio was facing the unique challenge of making "those frequent allusions to the customs and transactions of his own times, which render his writings so interesting... at a period when the Latin language was just rescued from the grossest barbarism... the writings of Poggio are truly astonishing. Rising to a degree of elegance, to be sought for in vain in the rugged Latinity of Petrarca and Coluccio Salutati..." His knowledge of the ancient authors was wide, his taste encompassed all genres, and his erudition was as good as the limited libraries of the time allowed, when books were extremely rare and extraordinarily expensive. Good instruction in Greek was uncommon and hard to obtain in Italy. Proficient teachers, such as Ambrogio Traversari, were few and highly valued.Manuel Chrysoloras

Manuel (or Emmanuel) Chrysoloras ( el, Μανουὴλ Χρυσολωρᾶς; c. 1350 – 15 April 1415) was a Byzantine Greek classical scholar, humanist, philosopher, professor, and translator of ancient Greek texts during the Renaissance. Se ...

used to be occasionally credited as having instructed Poggio in Greek during his youth, but Shepherd cites a letter by Poggio to Niccolò Niccoli stating that he began the study of Greek in 1424, in Rome at age 44 (Shepherd, p. 6). Poggio's preface to his dialogue ''On Avarice'' notes that his task was made the harder "because I can neither translate from the Greek language for our benefit, nor are my abilities such that I should wish to discuss in public anything drawn from these writings" Consequently, his knowledge of Greek never attained the quality of his Latin. His best-efforts translation of Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, wikt:Ξενοφῶν, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Anci ...

's ''Cyropaedia

The ''Cyropaedia'', sometimes spelled ''Cyropedia'', is a partly fictional biography of Cyrus the Great, the founder of Persia's Achaemenid Empire. It was written around 370 BC by Xenophon, the Athenian-born soldier, historian, and student of Soc ...

'' into Latin cannot be praised for accuracy by modern standards. But he was the first critic to label it a "political romance", instead of history. He also translated Lucian

Lucian of Samosata, '; la, Lucianus Samosatensis ( 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer

Pamphleteer is a historical term for someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (and therefore ...

's ''Ass'', considered an influence of Apuleius

Apuleius (; also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis; c. 124 – after 170) was a Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He lived in the Roman province of Numidia, in the Berber city of Madauros, modern-day ...

's Latin masterpiece, ''The Golden Ass

The ''Metamorphoses'' of Apuleius, which Augustine of Hippo referred to as ''The Golden Ass'' (''Asinus aureus''), is the only ancient Roman novel in Latin to survive in its entirety.

The protagonist of the novel is Lucius. At the end of the no ...

''.

Invectives

Among contemporaries he passed for one of the most formidablepolemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topics ...

al or gladiatorial rhetoricians; and a considerable section of his extant works is occupied by a brilliant display of his sarcastic wit and his unlimited inventiveness in "invectives". One of these, published on the strength of Poggio's old friendship with the new pontiff, Nicolas V, the dialogue ''Against Hypocrites'', was actuated by a vindictive hatred at the follies and vices of ecclesiastics. This was but another instance of his lifelong obstinate denouncing of the corruption of clerical life in the 15th century. Nicholas V then asked Poggio to deliver a philippic against Amadeus VIII, Duke of Savoy

Amadeus VIII (4 September 1383 – 7 January 1451), nicknamed the Peaceful, was Count of Savoy from 1391 to 1416 and Duke of Savoy from 1416 to 1440. He was the son of Amadeus VII, Count of Savoy and Bonne of Berry. He was a claimant to the papac ...

, who claimed to be the Antipope Felix V

Amadeus VIII (4 September 1383 – 7 January 1451), nicknamed the Peaceful, was Count of Savoy from 1391 to 1416 and Duke of Savoy from 1416 to 1440. He was the son of Amadeus VII, Count of Savoy and Bonne of Berry. He was a claimant to the papa ...

— a ferocious attack with no compunction in pouring on the Duke fantastic accusations, unrestrained abuse and the most extreme anathemas.

''Invectivae'' ("Invectives

Invective (from Middle English ''invectif'', or Old French and Late Latin ''invectus'') is abusive, reproachful, or venomous language used to express blame or censure; or, a form of rude expression or discourse intended to offend or hurt; wikt:vitu ...

") were a specialized literary genre

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other for ...

used during the Italian Renaissance, tirades of exaggerated obloquy aimed at insulting and degrading an opponent beyond the bounds of any common decency

Respect, also called esteem, is a positive feeling or action shown towards someone or something considered important or held in high esteem or regard. It conveys a sense of admiration for good or valuable qualities. It is also the process of ...

. Poggio's most famous "Invectives" were those he composed in his literary quarrels, such as with George of Trebizond

George of Trebizond ( el, Γεώργιος Τραπεζούντιος; 1395–1486) was a Byzantine Greek philosopher, scholar, and humanist. Life

He was born on the Greek island of Crete (then a Venetian colony known as the Kingdom of Candia), an ...

, Bartolomeo Facio

Bartolomeo Facio (c. before 1410 – 1457), Latinized as Bartholomaus Facius, was an Italian historian, writer and humanist.ometimes "Fazio'"> ''Dictionary of Art Historians'': "Facio, Bartolomeo

,_and_Antonio_Beccadelli_(poet).html" ;"title="ometimes "Fazio' latinized as, Facius, Bartho ...Francesco Filelfo

Francesco Filelfo ( la, Franciscus Philelphus; 25 July 1398 – 31 July 1481) was an Italian Renaissance humanist.

Biography

Filelfo was born at Tolentino, in the March of Ancona. He is believed to be a third cousin of Leonardo da Vinci. At th ...

and also Niccolo Perotti pitted him against well-known scholars.

Humanist script

Poggio was famous for his beautiful and legible book hand. The formal humanist script he invented developed into

Poggio was famous for his beautiful and legible book hand. The formal humanist script he invented developed into Roman type

In Latin script typography, roman is one of the three main kinds of historical type, alongside blackletter and italic. Roman type was modelled from a European scribal manuscript style of the 15th century, based on the pairing of inscriptional ...

, which remains popular as a printing font today (his friend Niccolò de' Niccoli's script in turn developed into the Italic type

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting. Owing to the influence from calligraphy, italics normally slant slightly to the right. Italics are a way to emphasise key points in a printed tex ...

, first used by Aldus Manutius

Aldus Pius Manutius (; it, Aldo Pio Manuzio; 6 February 1515) was an Italian printer and humanist who founded the Aldine Press. Manutius devoted the later part of his life to publishing and disseminating rare texts. His interest in and preserv ...

in 1501). Berthold Louis Ullman, ''The origin and development of humanistic script,'' Rome, 1960, p. 77

Works

* ''Poggii Florentini oratoris et philosophi Opera : collatione emendatorum exemplarium recognita, quorum elenchum versa haec pagina enumerabit,'' Heinrich Petri ed., (apud Henricum Petrum, Basel, 1538) * ''Poggius Bracciolini Opera Omnia'', Riccardo Fubini ed., 4 vol. ''Series: Monumenta politica et philosophica rariora''. (Series 2, 4–7; Torino, Bottega d'Erasmo, 1964-1969) * ''Epistolae'', Tommaso Tonelli ed. (3 vol., 1832–61); Riccardo Fubini ed. (1982, re-edition of vol. III of ''Opera Omnia'') * ''Poggio Bracciolini Lettere'', Helen Harth ed., Latin and Italian, (3 vol., Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1984-7) * ''The Facetiae'', Bernhardt J. Hurwood transl. (Award Books, 1968) * ''Facetiae

The ''Facetiae'' is an anthology of jokes by Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459), first published in 1470. It was the first printed joke book. The collection, "the most famous jokebook of the Renaissance", is notable for its inclusion of scatological ...

of Poggio and other medieval story-tellers'', Edward Storer transl., (London: G. Routledge & Sons & New York: E.P. Dutton, 1928Online version

*

Phyllis Goodhart Gordan

Phyllis Walter Goodhart Gordan (4 October 1913 - 24 January 1994) was a rare book and manuscript collector and a leading scholar of the Renaissance, known for her research into the life of Poggio Bracciolini.

Personal life and education

Phyll ...

transl., ''Two Renaissance Book Hunters: The Letters of Poggius Bracciolini to Nicolaus De Niccolis'' (Columbia Un. Press, 1974, 1991)

* Beda von Berchem transl., ''The infallibility of the Pope at the Council of Constance; the trial of Hus, his sentence and death at the stake, in two letters'', (C. Granville, 1930) (The authenticity of this work is in debate since the earliest edition discovered was in German in the 1840s.)

Notes

References

*Further reading

* Albert Curtis Clark, "The Literary Discoveries of Poggio", ''Classical Review'' 13 (Cambridge, 1899) pp. 119–30. * Dr. William Shepherd, ''Life of Poggio Bracciolini''1837 edition available online

, the most extensive and authoritative English-language biography to date. * Georg Voigt, ''Wiederbelebung des classischen Alterthums oder das erste Jahrhundert des Humanismus'' (3d ed., Berlin, 1893), gives a good description of Poggio's place in history. *

John Addington Symonds

John Addington Symonds, Jr. (; 5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the Renaissance, as well as numerous biographies of writers and artists. Although m ...

, ''The Renaissance in Italy'' (7 vol., Smith, Elder & Co, 1875–86), a historical perspective with a detailed description of Poggio's life.

* Ernst Walser, ''Poggius Florentinus: Leben & Werke'' (Berlin, 1914; Georg Olms, 1974; Nabu Press, 2011) 592 p. The most complete biography to-date, with more recent, accurate, and detailed information than William Shepherd's, but not translated into English.

* Riccardo Fubini & S. Caroti, eds., ''Poggio Bracciolini 1380–1980 - Nel VI centenario della nascita'', Latin and Italian, (Florence: Sansoni, 1982)

* Riccardo Fubini, ''Humanism & Secularization: From Petrarch to Valla'', transl. Martha King, (Duke Un. Press, 2003; original edition, Bulzoni, 1990)

* Riccardo Fubini, ''L'umanesimo italiano e i suoi storici: Origini rinascimentali, critica moderna'', (F. Angeli, 2001)

* Riccardo Fubini, ''Italia quattrocentesca: Politica e diplomazia nell'eta di Lorenzo il Magnifico'', (F. Angeli, 1994)

* Benjamin G Kohl; Ronald G Witt; Elizabeth B Welles, ''The Earthly republic : Italian humanists on government and society'' (Un. of Pennsylvania Press, 1978)

* Ronald G. Witt, "The Humanist Movement", in Thomas A. Brady, Jr., Heiko A. Oberman

Heiko Augustinus Oberman (1930–2001) was a Dutch historian and theologian who specialized in the study of the Reformation.

Life

Oberman was born in Utrecht on 15 October 1930. He earned his doctorate in theology from the University of Utrecht ...

, & James D. Tracy, eds. ''Handbook of European History 1400-1600: Late Middle Ages, Renaissance & Reformation'' (E.J. Brill, 1995), pp. 93–125.

* Ronald G. Witt, ''In the Footsteps of the Ancients: The Origins of Humanism from Lovato to Bruni, Studies in Medieval and Reformation Thought'', (ed. Heiko A. Oberman, E.J. Brill, 2000)

* Ronald G. Witt, ''Italian Humanism and Medieval Rhetoric'', (Ashgate Variorum, 2002)

* Harald Braun,In Defense of Humanist Aesthetics: Ronald G. Witt’s Study of Early Italian Humanism

, (''H-Net Reviews'', March 2003) * Ronald G. Witt, ''The Two Latin Cultures and the Foundation of Renaissance Humanism in Medieval Italy'' (Cambridge Un. Press, March 2012) * John Winter Jones, trans.,''Travelers in Disguise: Narratives of Eastern Travel by Poggio Bracciolini and Ludovico de Varthema'', (Harvard Un. Press, 1963), intr. by Lincoln Davis Hammond. * John W. Oppel, ''The moral basis of Renaissance politics : a study of the humanistic political and social philosophy of Poggio Bracciolini, 1380-1459'' (Ph.D. thesis, Princeton Un., 1972) * Nancy S. Struever, ''The Language of history in the Renaissance : rhetoric and historical consciousness in Florentine Humanism'' (Princeton Un. Press, 1970) * A. C. de la Mare, ''The handwriting of Italian humanists / Vol. I, fasc. 1, Francesco Petrarca, Giovanni Boccaccio, Coluccio Salutati, Niccolò Niccoli, Poggio Bracciolini, Bartolomeo Aragazzi of Montepulciano, Sozomeno of Pistoia, Giorgio Antonio Vespucci'' (Oxford University Press, 1973) * Louis Paret, ''The annals of Poggio Bracciolini and other forgeries'', (Augustin S.A., 1992) * John Wilson Ross, ''Tacitus and Bracciolini. The Annals forged in the XVth century'', (Diprose & Bateman, 1878) *

Anthony Grafton

Anthony Thomas Grafton (born May 21, 1950) is an American historian of early modern Europe and the Henry Putnam University Professor of History at Princeton University, where he is also the Director the Program in European Cultural Studies. He i ...

, ''Commerce with the Classics: Ancient Books and Renaissance Readers'', (Un. of Michigan Press, 1997)

* Anthony Grafton, ''Forgers and Critics: Creativity and Duplicity in Western Scholarship'', (Princeton Un. Press, 1990)

* Stephen Greenblatt

Stephen Jay Greenblatt (born November 7, 1943) is an American Shakespearean, literary historian, and author. He has served as the John Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University since 2000. Greenblatt is the general edit ...

, '' The Swerve: How the World Became Modern'', (W.W. Norton, 2011). Poggio's discovery of Lucretius's ''De rerum natura

''De rerum natura'' (; ''On the Nature of Things'') is a first-century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius ( – c. 55 BC) with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some 7 ...

''.

* Douglas Biow, ''Doctors, Ambassadors, Secretaries: Humanism and Professions in Renaissance Italy'' (Un. of Chicago Press, 2002)A

* L.D. Reynolds & N.G. Wilson, ''Scribes and Scholars: A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature'' (Oxford Un. Press, 1968)

* Brian Richardson, ''Printing, Writers and Readers in Renaissance Italy'', (Cambridge Un. Press, 1999)

* Ann Proulx Lang, Poggio Bracciolini's De Avaritia - A Study in 15th-century Florentine Attitudes Toward Avarice and Usury

' (Thesis, M.A., Sir George Williams Un., Montreal, 1973). Examination of the economic aspects of Poggio's Florentine life. * Remgio Sabbadini,

Le scoperte dei codici latini e greci ne' secoli 14 e 15

', Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1914. Discoveries of Latin and Greek codices in the 14th and 15th centuries.

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Bracciolini, Gian Francesco Poggio 1380 births 1459 deaths Italian Renaissance humanists Italian classical scholars Book and manuscript collectors 15th-century Italian writers Italian male writers Greek–Latin translators People from the Province of Arezzo 15th-century Latin writers